This is the 8th in the series, “War Through My Eyes.” After Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine, Oleg spent 20 months fundraising, purchasing, and delivering critical supplies for frontline troops. In December, 2023, he stepped up for military service and began sending in these essays.

FOOTNOTES

* A “ruscist” is a follower of the ideology of Ruscism (“Russian fascism”). “Orc” is a derogatory slang term for Russian military personnel.

** Mongolic ethnic group native to southeastern Siberia who speak the Buryat language. They are one of the two largest indigenous groups in Siberia

*** The Luhansk People’s Republic or Lugansk People’s Republic[c] is an internationally unrecognized republic of Russia in the occupied parts of eastern Ukraine’s Luhansk Oblast, with its capital in Luhansk.[4][5] The LPR was proclaimed by Russian-backed paramilitaries in 2014, and it initially operated as a breakaway state until it was annexed by Russia in 2022.

Oleg and his supporters are currently raising funds for needed supplies for their brothers-in-arms. You can donate via Oleg’s PayPal address veretskaya2009@gmail.com. The current push is for an anti-drone gun (see Twitter post).

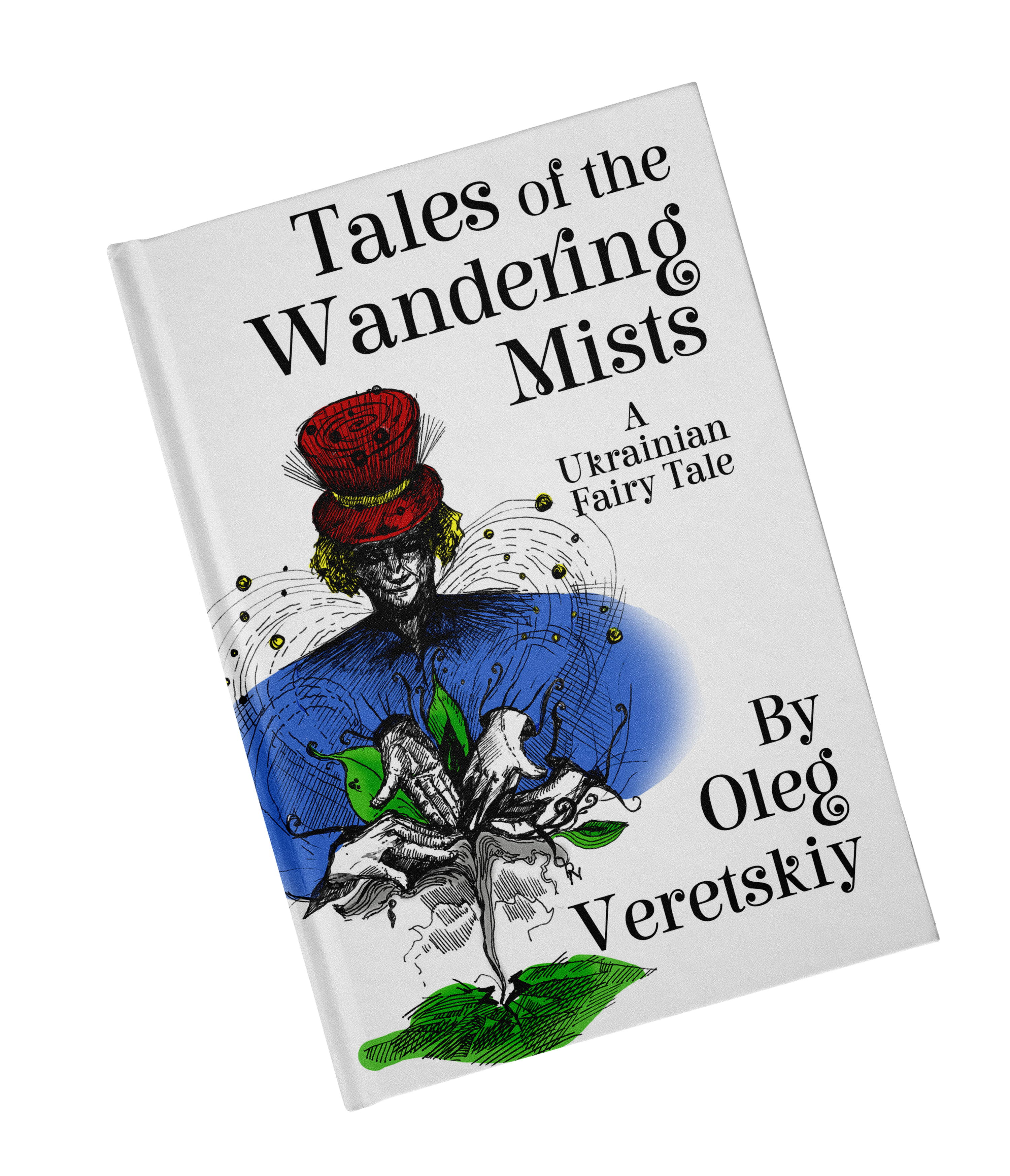

Author Oleg Veretskiy suspended his career to support his country’s fight for freedom. Thank you for helping publish his mythical coming-of-age tale! The first book in his trilogy is scheduled for publication in September. The “War Through My Eyes” stories will be collected in a future book.

“…for the lives of our people.”

The boastful pot-bellied driver spun the tattered steering wheel of the minibus as if he were performing a “Fast and Furious” stunt—rather than transporting humanitarian cargo to the recently de-occupied Kherson region.

“All sorts of things happened.” Our driver loved to chat, but not so much to listen. “Under occupation, this little bus and I carried refugees out of Kherson. Many people wanted to do the same, but few could manage it. Ruscist* checkpoints everywhere. Not knowing where anyone stands, it’s hard to figure out right away if the person in front of you is with the Ukrainian military or with those club-footed bastards. Drunken Buryat** conscripts or the LPR*** occupiers were often dressed in pixel camo, their insignia patches hard to read from a distance. But I knew who stood where and knew how to negotiate my way around with them all.”

“The orcs* too?” one of our guys asked darkly, sitting in the back.

“They were simple.” Pot Belly shrugged his shoulders. “You find the right officer. You give him a hefty bribe. Add vodka, and he figures everything out for you. You can’t get them to do anything without the vodka.”

“Wasn’t it repulsive to negotiate with these bastards?” Our guy in the back persisted with his questioning.

“At first it was repulsive and then I got used to it. It’s for the lives of our people. One could be proud and honest, and then our people would stay there, under occupation. For life.” He sharply turned the steering wheel, avoiding a pothole, and continued his story. “I know of one case where a young man decided to make some cash. He knew that people would give up their last change just to be able to escape that hellhole. Begged his father-in-law to borrow his van, filled the trunk with alcohol and cigarettes, and went to Kherson. But he never even made it to the city. On the way over, the bastard was stopped at the first checkpoint, stripped, beaten, and robbed of his cigarettes, vodka, and even the van. Then they sent him on his way on foot. And that’s how the drivers found him later: walking naked on the broken down road toward Mykolaiv. Good that he was left alive. Let it be a lesson to this bastard for the rest of his life—You can’t profit off someone else’s suffering.”

“Karma,” I smirked.

“And there was this other time, too.” Pot Belly took off his cap, wiped his sweaty face with it, pulled it back on his head, and continued. “I was driving—carrying 14 passengers. Among them, kids—two girls, a few older ladies, and a grandpa with a missing leg. It was dusk.

“Suddenly, we approached a checkpoint. What’s more, it was in a spot where there wasn’t one before. I looked closely, but couldn’t decipher the color or the pattern of the uniform. On the sleeves I couldn’t see the blue or yellow fabric of our Ukrainian soldiers, or the white ones like the orcs wear. I stop the van. One of them approaches the vehicle on the driver’s side and enunciates ‘Glory to Ukraine!’ with a strange voice. Instinctively, I understood that this was a provocation, because I once saw the Buryats mimic this greeting to everyone at a checkpoint.

“Those who responded with, ‘Glory to the heroes!’—were thrown out of their cars, stripped and thrashed. And other times they took all their property, stripped and tortured them on the spot. They would even shoot them. Not always, but often. Others were lucky and passed the checkpoint without incident.”

“Did they often beat them just for speaking these words?”

“I’ve seen it happen pretty frequently.” The driver took a deep breath. “So I learned from the mistakes of others. You know, boys, I’m no hero. I’m just a person. I’m afraid of pain and threats. I’m afraid of death. But I can act despite it.”

“So, what did you tell him?”

“I said, ‘Good evening.’ It was the easiest. The orc’s* face showed disappointment. Apparently he wanted to catch some Ukrainian patriot and take out his anger on him. But I was thinking about the passengers sitting in the minibus. He tried a few more times to provoke some conflict, but I avoided the phrases that would anger him. Then he ordered me to open the doors so that he could speak with every passenger individually.

“I felt nauseous, remembering that one of the girls in the backseat had a tattoo of a Ukrainian trident on her wrist. It would certainly cause problems. I said to him, quietly but with resolve, ‘Excuse me, sir, but I have an arrangement with your superior officer,’ and gave him the name of this officer. The katsap’s face turned sour, as if he bit into the world’s bitterest lemon. He called his partner over and they whispered about something on the side. Then the whisper turned into a heated argument.

“Finally, the one who stopped us spat angrily and walked away, while his friend approached the driver’s window and recited through gritted teeth, ‘And if I call him right now, will he confirm your arrangement?’ ‘Please do call!’ I said as everything in my chest churned violently. You understand, an agreement with the orcs is not worth much. He walks away a few feet and begins to talk into his walkie-talkie. I can hear from the van someone cursing him out. When the conversation ends, he stands there for some time, as if catching his breath. Then he turns back toward the minibus.

“‘Fine, I’ll let you through, but you have to make a deal with me.’ His smile took a cruel turn. ‘They say you are a transporter and pass through here all the time. Let’s make an agreement. Every time you pass by here, you give me five bottles of vodka and a block of cigarettes, and I will close my eyes to the fact that you’re carrying your swine passengers. Agreed?’ I nodded.

“‘Good doggie, well-behaved!’ he praised me and waved his arm to pass me through.

“Had it been peacetime, I would have beaten his face in for these words, but now I wouldn’t even take an extra step without getting shot on the spot. Or worse.”

“Worse?” Our guy from the back seat asked. “What can be worse than death?”

“Listen up and I’ll tell you, so you can understand for yourself,” the driver answered. “One time I was transporting a woman. I think her name was Galya. She told me about how she was evacuating with her young daughter during the occupation. I don’t remember exactly where from and where to. But here’s what happened.

“Katsaps stopped the column of cars that they were in. They were either looking for Ukrainian patriots or just searching cars for their own shits and giggles. They spilled out all of her bags and packages—even ripped open her children’s toys.

“They confiscated her phone, the money, the lunchbox with sandwiches, an emergency kit, her clean underwear, an old bra, and an open box of condoms—probably to send it over to their orc* women. Everything else they threw into the swamp nearby. Then they moved on to the next car. At that point, Galya’s daughter asked to go to the bathroom—They’d been on the road for a long time.

“Galya saw a small concrete structure next to the checkpoint and asked the katsap for permission to take her child to use the toilet. He gave her a sinister smile and waved his hand. The woman picked up the child in her arms and ran to the building. But inside, a real horror awaited her— A broken body lay on the soiled floor in a pile of bloody garbage. It was a man wearing military pants. His torso and feet were bare. Judging by his appearance, he had been beaten, cut and stabbed. Not a single visible part of him was clear of bruises and deep wounds.

“And yet, he was still breathing.

“Galya covered her daughter’s eyes with her palms to shield her from the horror. She took a few steps back, and bumped into that same orc who waved his hand to send her to the bathroom. He growled hideously and pointed to the body. ‘Go ahead, piss on him!’ Galya screamed, then tried to jump out of the building, but the orc grabbed her by the elbow and hissed into her ear, ‘Piss on him or I’ll rape your puppy right in front of you!’ Who knows what would have happened if the heavy shelling had not started just then. It was our guys hitting the katsaps. The orc turned white with fear, let go of Galya and ran outside.

“She carefully looked out and saw the katsaps running to their cars. Then, without hesitating for a second, she rushed to her car, put her daughter in the back seat and jumped behind the wheel. Our guys then gave those scumbags a good beating, hitting their equipment, which was nearby in the landing. The enemy tank tried to bite back, striking randomly, here and there. One of his shells flew into the same concrete structure, destroying the traces of yet another crime of the occupiers. That battle saved Galya and her daughter. They escaped.”

“I think that even though they got out of that hell, some part of their psyche will forever remain a prisoner of that concrete torture chamber,” I said. “This is impossible to forget.”

All content on this site © 2023-2024 by Oleg Veretskiy and Pierce Press. All rights reserved.

Direct Inquiries To:

PIERCE PRESS

P.O. Box 206

Arlington, MA 02476

+1 339-368-5656

Copyright Oleg Varetskiy/Pierce Press 2020-2023 Design by Laura Williams Pages